By Christina M. Stetler

Membership & Annual Giving Coordinator, Pennsylvania Heritage Foundation

In the fall of 1918, the war to end all wars raged in Europe. The United States, having joined the war in 1917, hoped their entrance would bring a swift conclusion to a battle-worn Europe. The war would end in November 1918, but not before death encircled the globe.

Medical professionals in the spring of 1918 recorded an unusual flu season. Doctors in Haskill, Kansas, noted an uptick in cases with symptoms unlike the typical flu season, though there were not an abnormal number of deaths. A doctor in Kansas mailed his notes to the Board of Health in Washington, D.C., which indicated he was concerned with what he saw. This act itself was uncommon, as influenza was not a mandatory reportable disease in the spring. This would change come September.

The summer months were quiet. Cases of influenza were few during the months of June, July, and early August. By the end of the month, the influenza virus from the spring returned, but more virulent and deadly.

The first indication of the coming calamity came from the Boston Naval Yard. In late August, men began going to the naval hospital complaining of illness. A few at a time, then a steady stream. So many coming in daily, that tents were set up to accommodate the ill.

While many navy personnel visited the hospital and medical tents popped up in ever growing numbers, the war effort continued and ships left the Navy Yard for American and European ports. One such vessel sailed to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, arriving on September 6. This ship carried the influenza virus into Philadelphia, leading to the deadliest outbreak of any U.S. city.

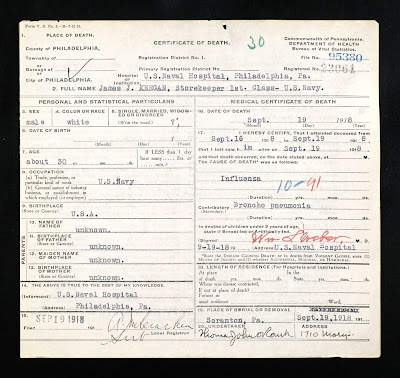

Once docked in Philadelphia, several sailors went immediately to the Naval Hospital complaining of flu symptoms. As in Boston, as the days went on, more sailors started developing symptoms and needing medical assistance. According to the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, on September 19, three sailors from the Navy Hospital passed away from the virus: James J. Keegan, Storekeeper 1st Class; Richard Singleton, Chief Boatswain’s Mate; and Mark J. Harrison, Fireman 1st Class. On the date of publication, there were 565 total cases of influenza at the Navy Yard and the 4th Naval District, with 136 cases presenting the previous day.

|

| Death certificate for James J. Keegan, who died of influenza Sept. 19, 1918, in the U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia |

Shortly after the first deaths attributed to the outbreak were recorded, the Board of Health required influenza to be a reportable disease. Doctors were now required to report cases and isolate patients to try to curb the spread of the disease. Initially, this was to be only a temporary measure, but the requirement to report influenza cases continues to this day.

|

| Liberty Loan Parade at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 28 September 1918 (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command NH41730) |

This would be disastrous to the city and its citizens. Within days, the number of ill jumped to 635 new cases, with more being reported hourly. The city needed to take strong measures to curb the disease and on Thursday, October 3, the Philadelphia Board of Health closed all public schools and canceled all outdoor Liberty Loan meetings. [Editor's note: "Parade to Raise Money for World War I Brought Deadly Influenza to Williams Valley in 1918," on the Wynning History blog, explores a similar situation in a smaller Pennsylvania community.] With the number of ill and dead mounting, the Board of Health also closed all saloons, theaters, and churches.

The Story Continues

Early in October, to help combat the disease and provide desperately needed support, the Most Reverend Archbishop D.J. Dougherty granted permission to non-cloistered nuns of the diocese to go into “the local communities and mission houses, in order to thus relieve suffering, and control conditions which were baffling the best efforts of the medical profession and city authorities in private homes, in general and emergency hospital and public institutions.” These nuns would leave one of the most telling records of the influenza outbreak, “Work of the Sisters during the Epidemic, October 1918.”

Sisters from St. Leonard’s Academy assisted in the Philadelphia General Hospital, Blockley. The first day, a sister wrote, “Some of the poor sick had had no attention for eighteen hours, and some had not been bathed for over a week.” At Emergency Hospital No. 8 at 1726 Broad Street, a sister noted one of her patients endured tremendous suffering. As she assisted the woman in undressing, “the flesh from her body fell off in my hands. It seems the people at home had put coal oil on her to ease the pain. She lived four days in that agony.”

This report is one of the few to survive. The reason? The diocese knew that “facts unrecorded are quickly lost in the new interest of changing time. Incidence of personal experience, even the most touching and pathetic, pass away generally with the memory of those immediately concerned.” Other than newspaper articles, medical and military reports, and the occasional personal experience, it is difficult to find information on the epidemic. The report of the Sisters in Philadelphia is one of the best first-hand accounts available.

As the month moved on, more and more people fell ill and many succumbed to the virus. Those who were affected found themselves ill very suddenly. Patients would “feel… weak, [have] pains in the eyes, ears, head or back, and may be sore all over. Many patients feel dizzy, some vomit. Most of the patients completely feeling chilly, and with this comes a fever in which the temperature rises to 100 or 104. In most cases the pulse remains relatively slow. In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and inner side of his eyelids may be slightly 'bloodshot' or 'congested,' as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough.”

The number of dead accumulated faster than could be accommodated in the city morgue and outpaced the number of available coffins. Many bodies piled up waiting for the mortician to properly prepare the dead for burial. This would cause a spike in coffin and burial costs, so egregious that the city would crack down on the inflation. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin reported some were charging $15.00 for burial, even if the family dug the grave. The city stepped in and set the price at $9.00, unless the cemetery dug the grave, in which case, the cost could be $14.00.

By mid-October, the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin stated a death toll of 10,301 due to influenza in the previous three weeks. At this point, the number of cases reported and the number of deaths began to decline. And as they did, the citizens called for the reopening of schools, churches, and saloons. By October 24, Dr. Krusen believed the ban should be lifted, but he needed the permission of Dr. Franklin Royer, acting Pennsylvania Commissioner of Health. Dr. Royer advised against such action, but did not interfere.

Churches and synagogues were to open October 26 with services being allowed on Sunday, but no Sunday School. Schools would all open by the following Monday, October 28. Theater and motion picture houses, saloons, and wholesale liquor stores received permission to open on Wednesday, October 30th.

The epidemic would wind down in the next few months. There was a flare up after the armistice was signed and announced on November 11 due to celebrations bringing people into the streets and in close contact again. But, unlike what happened during the Fourth Liberty Loan parade, the virus seemed to have lost its virulence. December also showed an uptick in cases, but nowhere near the total number of deaths were attributed to it. The mutated influenza virus that hit the world in September and October seemed to release its grip and now began to return to the type of illness people were familiar with. The same influenza strain appeared in the spring of 1919, but the dark months in the previous fall would not return.