The Pennsylvania State Archives collects, preserves, and makes available for study the permanently valuable public records of the Commonwealth as well as papers of private citizens and organizations relevant to Pennsylvania history. The Archives has almost 235 million pages of records and about 1 million photographs, maps and other special media. In this week’s guest post, Archives intern Corine Lehigh shares the story of how one collection of documents made its way from a garage in Merion Station (Montgomery County) to the 14th floor of the State Archives tower (and teaches us some basics of archival management).

Appraisal

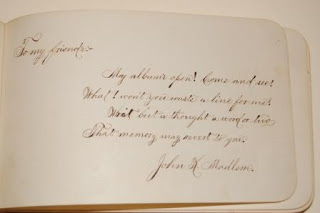

Earlier this year Richard Shapp, son of former

Pennsylvania Governor Milton J. Shapp (1912-1994), contacted the State Archives about donating some of his father’s personal papers, then housed in two five-foot-tall filing cabinets in his garage. The first step in the records acquisition process is appraisal. An archivist has to determine the historical value of records based on several different criteria including research potential, age/scarcity, and the size of the collection. Knowing that the information in those filing cabinets would help to fill out

Manuscript Group 309, the Milton J. Shapp Papers, Archives Director David Carmicheal gladly accepted the donation.

|

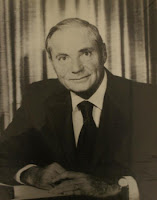

| Milton J. Shapp, Governor of Pennsylvania 1971-1979 (PA State Archives) |

On June 30 archivist Richard Saylor and I headed to Merion Station to pick up the records. With the necessary paperwork already completed, it was to be a simple retrieval.

Richard Shapp was very knowledgeable regarding not only his father’s political career but also many events of the 1970s and 1980s. He told us about Gov. Shapp’s love for poetry and short stories—two whole filing drawers contained Milton Shapp’s own work—and shared many stories, including his father’s vision for the Peace Corps, which he shared with President John F. Kennedy in the early 1960s. One surprise we received was a folder of information regarding

First Lady Muriel Shapp (1919-1999), who had taught Japanese American high school students at the

Topaz internment camp in Utah during World War II. Listening to Richard Shapp talk about this collection as we packed it up made me want to process it and read into more detail all of the information we had received.

After we had packed up the van with over 11 cubic feet of papers, film reels and photographs, Mr. Shapp invited us to join him for lunch. While he got everything ready we viewed what his partner referred to as his “Forrest Gump” wall. I can completely see why she calls it that! The upstairs hallway was lined with photographs of our host with some very important people including Anwar Sadat, Queen Elizabeth II, Richard Nixon and Pope Paul VI. [Editor’s note: Shapp, classically trained in opera at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia,

has sung professionally in the U.S. and abroad, alongside such notables as Luciano Pavarotti and Anna Moffo.] Richard Shapp was more than just a donor; he was a generous host and a wealth of knowledge.

|

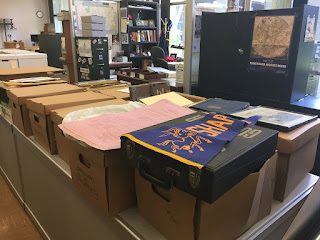

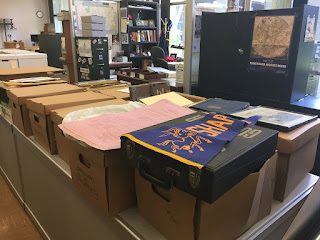

| Shapp collection before processing |

Accessioning

When a record is accessioned we are taking legal and physical custody of the materials and establishing intellectual control. Once the new Shapp acquisition was back at the Archives, our first step was to note, in a very general sense, what was in each box. Then Richard Saylor typed up an accession register that included all of the basic information we had gathered thus far: the source and origin, an estimated date range the boxes covered, how many cubic feet of material before processing and what manuscript group it would be accessioned into. From here the boxes and accession register were given to Kurt Bell, who is the Manuscript Group processor in the Collections Management section of the State Archives.

|

| Kurt Bell and Corine Lehigh examine records |

Processing

Processing is the arrangement, description, and housing of archival materials for storage and for use by patrons. First we sorted the boxes into subject groups alphabetically, and then I rehoused the documents into archival boxes. (It is important to use acid-free boxes and folders for long-term preservation; many general use folders and papers will begin to deteriorate rapidly as the years progress, leaving the records unusable.) Once the records were arranged, the next step in processing was to write a general description of the contents of each folder, bearing in mind what researchers would be looking for and what would help them use the materials. This necessitated dividing the groups by subject and then boxing them up in chronological order, which was especially important for files created during Gov. Shapp’s two terms in office.

|

| Records in new acid-free boxes |

Think about your own collection of personal items. It probably includes papers (essays you wrote in high school or college, letters from friends and family members, family recipes, etc.), photographs, videos (remember those

big clunky video cameras in the ‘80s?), and various objects (your varsity jacket from high school and maybe a yearbook, your first license plate or your wedding dress, things that were important to you). Now think about whether or not you have all of those things labeled (Central Michigan Univ. has

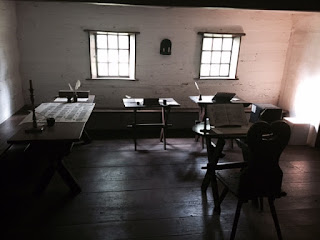

advice on storing your personal collections). Would a non-family member be able to determine why those items were important to you? That is what processing is: determining what and why someone kept something. It also involves a lot of research. For the Milton Shapp collection I had to listen to cassette tapes, flip through several reels of film and read many of Gov. Shapp’s creative works so that I was able to determine the what, why, when and how behind the collection.

|

| Researching film from Shapp collection |

Having properly housed the collection in acid free boxes and folders, arranged the collection logically for researchers to access, and answered all my questions, I moved the collection from my desk in the work room to the 14th floor of the Archives tower, with the rest of the Milton J. Shapp collection. Taking all of the information I had learned through my research I wrote a description of the series, which we decided to entitle “Personal Papers” and assign series number 309.15. Each series contains a description like the one I wrote, often called a scope and content note. The scope and content note is a narrative statement that summarizes the characteristics of the described materials and the types of information contained. I also included the names of people who appear in the collection besides Milton Shapp, again keeping in mind what a researcher would be looking for (like

John F. Kennedy or

Genevieve Blatt.)

|

| Creating a finding aid for Gov. Shapp's personal papers |

Once I was done writing my series description and had thoroughly edited my folder level descriptions for the finding aid, the information was given to Kurt Bell to upload to Archon, a digital archival management program.

A finding aid is a descriptive tool used to establish physical and intellectual control of archival material (meaning we know what it is and where we can find it). The finding aid outlines the materials located in a specific collection and can include guides, inventories, special lists, and container lists as well as biographical and historical information about the individual or organization.

So that’s how a record goes from being in someone’s garage to becoming available for a researcher. It’s an important process to help preserve records for future generations to enjoy. Hopefully this post also helps you think about your own collection of personal papers and how you can make it easy for future generations of your own family to enjoy.